Rooted is a photo book about the world of micro-gardens in refugee camps. These tiny patches of greenery appear wherever camp dwellers seek hope, solace and dignity in caring for plants and flowers.

Following Shelter and Ville de Calais, Rooted is the third and last part of an unintended trilogy on the lives of refugees and migrants. The three books were not conceived as a series sharing a preconceived structure or format, but are at most loosely related in content, photography and book design. The books Shelter and Ville de Calais arose independently, each telling a distinct story in its own narrative style and logic. And Rooted will be no exception. The soft cover book contains 164 pages and 74 images.

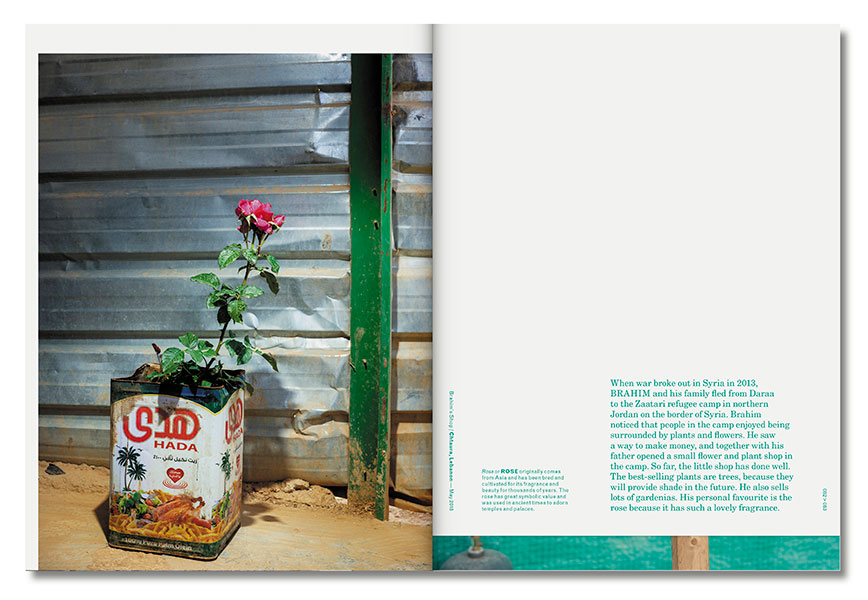

Rooted returns to a phenomenon that was already noted in Ville de Calais: the many refugee camp residents who find hope, consolation and dignity in nurturing a few plants. These miniature gardens are often little more than a few tin cans planted with flowers, or of a handful of seeds or bulbs struggling to sprout in a patch of meagre soil. Some residents will go so far as to hammer in a few stakes or construct a makeshift fence to mark off a temporary claim to a bit of territory. The phenomenon is not of course limited to Calais, for almost anyone who has been expelled from their homeland will eventually reconcile themselves to the unfamiliar ground where they have ended up. To me, the herbs, flowers and miniature gardens that they plant symbolize a longing for something resembling a normal existence.

Besides in Calais, I have in recent years photographed micro-gardens in refugee camps in Tunisia, Jordan and Lebanon. I also noted the stories of the gardeners. What emerged was not only the importance of a bit of greenery but also the way the temporariness of the camp dragged out into a seemingly permanent state, with little prospect of moving on or returning home. The reality of their permanent displacement gradually dawned on them. They were now stranded, with little choice but to put down roots in a foreign soil. Here they were tolerated although it was not where they wanted to be.

It was no solace to the camp dwellers that they were sometimes a mere 20 kilometres from their original home. The future they once saw as full of possibilities was now barred to them. Caring for herbs and flowers was often all they had to hold onto, to remind them of home, a comforting microcosm in an uprooted life.

DISPLACED GARDENS

Kenneth Helphand & Henk Wildschut

Pick up today’s paper. Tragically in too many places in the world, people are fleeing conflict, violence, famine and environmental catastrophe. In fear for their lives, seeking safety and security they have reluctantly fled. With fear, trepidation and courage, they assume a new identity as refugees. Left behind are their homes, the bulk of their possessions, their communities, and often family members. Propelled to an unknown destination, an uncertain future, and with minimal hope of returning home, they are relocated to camps and housed in makeshift structures and tents. Under strange and harsh conditions some of these refugees turn to garden making.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees -the UNHCR- this year said that there were 66 million displaced persons exceeding 50 million for the first time since WWII. Five million of those individuals are escaping the catastrophic civil war in Syria. When we speak of military landscapes we think of the battlefield and bases, but little of the landscapes created by war, places that are the consequence of war, the sites of conflict, destruction and devastation. The civilian victims, who greatly outnumber soldiers flee. Those who survive, and many do not, most often become displaced persons living in a refugee camp.

Conflict generates refugees. Libyans fleeing their civil war in 2011 as well as Sudanese who have trekked across the Sahara made the perilous crossing of the Mediterranean to Europe or over the border into Tunisia. Afghans have fled to Pakistan. Most dramatically almost a quarter of Syria’s 22 million people have fled the country and an even greater number have been internally displaced. Most of these refugees have crossed the border into Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon creating a humanitarian, environmental and political crisis in those nations.

On 8 October 2005 a major earthquake struck the Kashmir region in the north of Pakistan Classified as severe with a moment magnitude of 7.6, the quake was felt as far away Delhi and Afghanistan. An estimated 3 million people were left homeless and there were some 87 thousand fatalities. The images that reached me through the media were heartbreaking. Entire villages had been destroyed and in some cases completely buried by landslides.

A few weeks after the quake, the NGO Doctors Without Borders asked me to document and report on emergency aid in the afflicted region. I recognized the wretched conditions that prevailed there from images I had seen on TV, but I noticed something else that I had not been previously aware of. While media reporting on disasters like this tends to focus on the suffering and helplessness of the almost anonymous victims, I could see that there was actually a great deal of positive action and resilience. The emergency tents were, as the British say, kitted out with household necessities recovered from the rubble. Amongst the chaos of the camps people planted little gardens alongside the tents as a way of marking their private territory and manifesting their individuality. They were also a gesture towards reconstituting a community.

The occupants of these emergency tents were not merely victims but individuals who were trying to resume a normal life, as far as possible. My awareness of their need for order and domesticity only increased my empathy with the misery of the Pakistanis. I could never forget the sight of those newly planted vegetable patches between the emergency tents, although I was then not yet aware that small, informal gardens were a far from unusual phenomenon in refugee camps.

Returning to the Netherlands, I read that hundreds of refugees and illegal emigrants from Iraq, Afghanistan, Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan and Pakistan were bivouacking in the woods around the French harbor town of Calais. They regarded Calais as a departure point for the final leg of their long and often perilous journey: their hoped-for crossing to the UK, the destination of their dreams.

Since Calais is only 220 miles from my home base in Amsterdam, I decided to drive down there. In the woods around the city, the area came to be called “the Jungle”. I encountered congregations of small huts made of blankets, old clothes and waste materials of every kind, all carefully bound together with bits of string and tape. Despite the abject conditions under which they were living the migrants revealed the same resilience and determination I had first observed in Pakistan. Witness this remarkable Eritrean church

I documented their gardens; the Sudanese quarter of the camp was particularly rich in their creations.

But also, on successive visits over ten years the stages of construction, demolition, rebuilding and the ultimate demolition of the camp.

It was above all the expressive appearance of these makeshift homes that prompted me to portray the hidden world of the illegal immigrants. It led to several years of intensive work travelling the edges of Europe. That research concentrated largely on what were effectively transit camps. In these camps, I rarely encountered little gardens; the migrants presumably had no time to create them before they had to move on elsewhere.

A few years ago I was contacted by Henk who shared with me his photographs of gardens created by refugees in Jordan, Tunisia, Lebanon and France which has led to this fruitful collaboration to both picture and explain this phenomenon, for these are all defiant gardens.

These are pictures of gardens, but only occasionally does the unseen gardener make an appearance. Who are these refugees? Escaping a civil war, there are farmers and others with garden knowledge, but many are urbanites with little garden experience. Gardens, in deserts, prisons, hospitals, highway medians, vacant lots, rooftops, dumps, wastelands, cracks in the sidewalk, and refugee camps: these are examples of defiant gardens, gardens created in extreme or difficult environmental, social, political, economic, or cultural conditions. Normally taken for granted, these defiant gardens, created against all odds, astonish us by their mere presence, but we equally recognize the sheer force of will and effort that goes into their creation. I examined this phenomena in my book Defiant Gardens: Making Gardens in Wartime.

A premise of that book was that as psychologists and philosophers learn about human behavior by examining people in circumstances of deprivation and hardship. In the same way, gardens in extreme situations reveal essential aspects of the meaning of gardens. Gardens are always defined by their context. Perhaps the more difficult the context, the more accentuated the meaning. That is certainly true for refugee camps. These gardens represent adaptation to incredibly challenging circumstances, but they are also sites of assertion and affirmation. In times of crisis or difficulty, gardens have the potential to offer more than we have expected. Their latent capacities provide unanticipated forms of sustenance other than growing food. They provide food for the psyche and for some, balm for the soul. Caring for nature, even in this most modest form, can have a profound spiritual power.

The main str4eet of the Jungle in Calais.

While they are inanimate, gardens are not mute. In fact, what they have to say to us is quite inspirational. They testify to a depth of garden meaning amplified through hardship, a meaning that may lie latent in all garden creation, awaiting a catalyst to bring it to conscious awareness. Gardens are alive, they are a connection to home, they embody hope, and they are places of work and the sites of beauty and artistry. These are commonplace themes, but the meaning of each is magnified by the garden’s defiant response to conditions confronting the refugees.

After years of photographing poorly organized, makeshift refugee encampments, I felt it was time to take a look at an official camp organized by UNHCR. I travelled to Tunisia for this purpose in 2011. The Choucha refugee camp was located in desert land bordering Libya, and its main inhabitants were emigrants from Sudan, Somalia and Chad. An estimated 2.5 million people, roughly one-third the population of the Darfur area, have been forced to flee their homes after attacks by Janjaweed militia backed by Sudanese troops during the ongoing war in Darfur in western Sudan since 2003.

Despite the scorching desert heat in at Choucha, I was amazed to find little garden plots complete with garden ornaments all over the camp. I also witnessed how inhabitants personalized the standard tents provided by UNHCR. They would cut into the tent fabric in order to increase the height or to add on an entrance awning. Strangely, the public relations officer who guided me around the camp had never noticed these expressions of individuality. He seemed fixated on the victimhood of the camp inhabitants and was completely oblivious to the signs of their resistance to that stigma. The awareness of probably being fated to a long stay in the camp prompted a need among the inhabitants to distinguish themselves from the monotonous official surroundings. These little gardens were expressions of resistance to bureaucratically imposed victimhood.

It is important to note that while these gardens have great meaning to their makers and also to those who witness them they are only a modest respite from the conditions of the camps, and the plight of people loving in limbo, but that does not lesson their significance.

Home is not just a dwelling. In the deepest sense it is where one is from, and often a symbol of self and stability. These tent encampments are only a temporary “home”, but gardens are one way, and surely only one, that can help make an alien environment familiar. They also act as a mnemonic “homing” devices, conjuring reminders of places left behind. For individuals displaced – garden making is one way of placing oneself. In the alien, depersonalized, institutional environment of a refugee camp a garden can be one way personalize one’s environment, an assertion of identity and an opportunity to do something “normal” activity in the midst of indeterminacy and chaos. Within the refugee camp they can be a modest element that offers a temporary refuge or at least a respite from one’s condition.

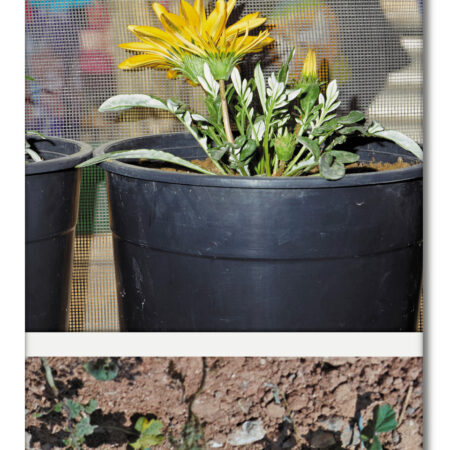

Following my experience in Choucha, I (Henk) travelled to the Zaatari camp in Northern Jordan on the border with Syria. It was first opened on 2012 and the camp has averaged some 90,000 inhabitants in recent years. In a horrific contest it varies between being the world’s second to fifth largest camp, the largest is now in Bangladesh for Rohingya refugees.. Like Choucha, Zaatari is located in a dry desert area. The soil contains a high level of salt making it practically unusable for arable use. Nonetheless, there are vegetables and herb gardens all around the camp. It is significant to note that the Zaatari refugee camp is gradually moving away from a model of top-down provision of services and even design, as a refugee camps administered by international humanitarian organizations. Instead, the camp is gradually transforming, into a more organic and more successful model of development into a self- organized urban conglomeration. These are cities in the making. Garden making is one small aspect of this transformation and assertion of local control.

The testimony of gardeners amongst Syrian refugees at Al Za’atari Camp in Jordan offer the most powerful evidence. The gardeners are explicit about what the gardens mean to them. Samar, says “When we garden we feel happy, because there’s something to do, such as watering the plants and such, it just makes you feel like there is life. Where we’re from we’re used to the view of greenery, here there’s nothing, it’s a desert. So, if there was a garden we feel like we’re home and it reminds us of our country. Adham says, “I miss my old life a lot, I cannot forget it,” he says. “Every time we think about it a little bit, we cry. Plants are for the soul. When you’re sitting in the garden, you feel like there are beings around you, and when plants bloom from the ground where there are no plants you feel like you’ve done something. When we see the green colors, we remember Syria. “

Garden is a verb as well as noun and the activity can carry equal, or even greater meaning and significance than the place itself. Defiant gardens are the product of defiant gardening, assertive and deliberate actions. Work can be productive, but it is also a way to keep one’s mind and body occupied. There is satisfaction and even therapeutic value that comes from manual labor. It fosters a sense of dignity, self-respect, and identity. Garden work can provide a sense of purpose; it is an act that provides relief from monotony, idleness, and restlessness—it can be something “to do” versus the boredom and idleness of refugees, removed not only from their homes and communities but also from their livelihood. Abu Qasem reports, “When I’m gardening I’m keeping myself occupied so that I don’t get to feel frustrated or angry, your psychology changes when you work with plants. This garden is an expression of love between one another, green is good.”

These gardens are intimate responses not only to a political situation, but also to the environment. These are all desert gardens. Thus, they address an environment with little or no water, poor soils, a scarcity of plants and seeds and limited building materials. They demonstrate an imaginative, ingenuous and creative responses to the situation and conditions. They are profound reminders that the urge to transform one’s surroundings is a basic human aspiration. They offer a rejection of suffering and are an inherent affirmation and sign of human perseverance. They demonstrate resilience, persistence, quiet strength, and simple dignity. They also display understated and modest beauty, for they are also acts of beautification amidst the desolation and often squalor of the camps. They are small scale acts of resistance – a kind of anti-camp.

All gardens are ephemeral. Made of natural materials and in need of maintenance, their existence is short-lived, their marks on the land quickly obliterated. The gardeners have clearly considered the making of their gardens, so it is incumbent upon us to seriously look at, consider and admire their ingenuity and creativity.

Marking the garden boundary or the territory of the tent that is “home”, the garden can offer a sense of ownership and pride in this small piece of terrain and way to claim this area as their own. The These gardens are all demarcated, Simplest are mounds of bermed earth or lines of stones, the ubiquitous rocky and sandy terrain of the camp that are cleared to make smoother surface in proximity to one’s dwelling. Discarded boxes, cans, fabric and more dramatic exercises to contain space are made with poles, stakes, bottles, fencing, wires, tarp, fabric. Plants and plants in containers are arranged to create an outdoor space that borders on being a patio. The materials are virtually all saved or scavenged in the camp recycled into another purpose.

It is tempting to equate size with significance, but a single potted plant may mean as much to its owner as large planted area to another. Perhaps unconsciously or consciously the awareness that they be forced to move at any moment the most common gardens are potted plants that could be moved if they are relocated within the camp or if one’s structure is destroyed or made uninhabitable. Single potted plants are most common, but some inhabitants array the pots as boundaries, as entry statements or as larger displays on shelves and… a collections of pot gardens. These recall one of the most ancient of garden types, the potted plants of Adonis garden display of the ancient Greeks.

Garden making is a creative activity. For some gardens making is an outlet for inspiration and craft. This can be as simple as ornamenting a single pot or a botanical display of plants and pots arrayed on the ground or even her in shelves. This image of plants juxtaposed against billboard like image is striking in the contrast yet all of these gardens are, for they are all inherently juxtaposed against the harshness and sterility of the camp environment. Gardens making is also a gesture of care. The plants need care, in these desert landscape at a minimum doses of water. The Sudanese camp dwellers bought seedlings in nearby villages and planted them in the desert sand of the camp. They used an ingenious system for irrigating their crops. Plastic water bottles would be filled with a mix of sand and water and thrust upside-down into the soil, so as to gradually dispense the moisture the plants needed to survive in the desert heat. It was a technique that they had learned in their Sudanese homeland. Many of the men I met in the camp had fled in the preceding years from Darfur, a province inhabited principally by nomadic tribes.

The many gardens in Zaatari are worrying to the UNHCR, for the camp’s water consumption is double that of a comparable Jordanian city. Despite that, the inhabitants continually complain about the shortage of water. Much of what is available is used for irrigating those near-impossible little vegetable plots. The camp’s thirst for water is also a source of aggravation to the Jordanian citizenry, who think it is wrong that so much water goes into accommodating their “guests”, a scarce commodity in a largely desert country like Jordan.

By contrast, there is no shortage of water in the Beqaa Valley in Lebanon. The Beqaa is a fertile agricultural region on the border with Syria and a mere 2 hours drive from the Syrian capital Damascus. Refugees living in the valley are scattered over small, poorly organized camps.

The Lebanese government is unwilling to give the refugees official aid because of concerns about permanent settlements being established. With a permanent population of about 5 million people, Lebanon houses an officially estimated 1 million Syrian refugees; in reality the latter number is much greater. Since the last two years, the Lebanese government has prohibited the official registration of new refugees with the UN in the hope of quelling unrest among the population.

Gardens need care and that care can be interpreted as a gesture to the community for they are public statements. Care inside the tent or dwelling is equally important for physical and psychological wellbeing, but these are private expressions.

Pot are common but many plant directly in the ground. Most planting is ornamental and even when vegetables are planted, mostly onions or garlic, they are planted in small furrows or mounds. The produce, if it matures can only provide a small supplement to the diet or rations. Where do they get plants? Some have brought a plant or seeds with them others are scrounged from the surrounding territory or purchased from locals.

There is a concept that can offer other insights to these displaced gardens, what geographers and ethnographers refer to as dooryard gardens. These vernacular gardens are those places right at the entry, the “dooryard” to a dwelling, in most refugee camps, that means the entry to a tent. At the doorway some gardens create an entry passageway, with plantings or objects directing and marking the entry. Some act as a makeshift forecourt or yard accommodating aspects of outdoor life. In the refugee camps the possibilities for dooryard gardens are limited, yet they still can become places for socializing, cooking and other household labors. They can even become the settings for camp commerce. One of the most common of the dooryard functions is clothes drying easily accomplished in the hot and dry desert climate and the garden boundaries act as clotheslines.

Most of the refugees do day work for farmers in the Beqaa Valley. That is probably why I found few vegetable gardens among the little gardens in the valley, but all the more flower gardens. Hind Bazzazi has lived in the Beqaa for over two years and sorely misses her large garden in Homs, which was full of dahlias and olive trees. Her favorite flower was jasmine but, she told me, it refused to grow in the Beqaa. Now she had cuttings planted in pots around her temporary shelter, reminding her of the flowers in her garden in Homs. The flowers are a comfort to her, making her feel a bit more at home.

Not far from Hind, I discovered a veritable oasis of plant pots and cuttings. It was almost like a florist’s shop. On inquiring, I learned that the oasis belonged to Walid Merhe and that the plants were not for sale. Walid told me that he loves his plants, and Hind her flowers, because it helps them rise above the unpleasant reality of their situation. Walid himself considers the cultivation of plants as vital to his mental survival. He needs a distraction to help him forget all the misery for a while. The sheer quantity of plants he has around him betrays the horrors of the past from which he has escaped. When I asked what his favorite flower was, he brought out two gardenias from his tent; he kept them inside because he is afraid they cannot thrive in direct sunlight. I can see his eyes light up a bit whenever talks about his plants, after which he quickly resumes the downcast gaze of a severely traumatized man.

After my visit to the Beqaa Valley, I recounted the story of Walid to a Lebanese friend. He recognized the Walid’s love of flowering plants because flowers were a symbol of hope to many Lebanese people caught up in the civil war that raged from 1975 to 1990. He told me that once the dust settled after savage artillery fire on his city, Beirut, the bakery was the first shop to open its doors to customers followed by the florist. Amid all the destruction, the sweet-scented vulnerability of flowers inspired hope among the war-weary residents of the city. My next mission as photographer is to photograph the flowers.